The northern provinces of the Netherlands, who rebelled against their legal ruler in the seventies of the sixteenth century, possessed great vitality and creative capacity despite their division and mutual conflict. The fundamental institutions that for two centuries formed the framework within which the life of the Republic would take place, came into being when the war was still a fierce battle for the rebellious cities themselves, which did not have the character of the organized campaigns, which later on were far from the heart of the Republic.

At that time it was all about speed and decisiveness. The university in Leiden was established four months after the termination of the siege of that city. Ten years later, one of the professors in theology at the newly established university in Franeker was advised by a friend to start his lectures by dealing with one of the smaller letters from the New Testament. If he worked fast enough, he might be able to complete his subject before the end of the revolt in Friesland, perhaps the end of the Frisian university.

As one of the four hundred-year commemorative collections that appear steadily during these years, the University of Franeker articles 1585-1811 will be offered tomorrow . More than with its counterpart from ten years ago, Leiden University in the Seventeenth Century, an Exchange of Learning , the editors have strived for thematic unity, and despite the large number of articles (thirty-three) they have succeeded reasonably well. The first part, in particular, which sheds light on the relationship between university and society, is very successful and a stimulating example of modern university historiography. The second part contains articles about the history of science of the four faculties: theology, law, medicine and liberal arts and literature.

Franeker and Leiden were part of the wave of new universities of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which were no longer founded by the universal powers of Pope and Emperor, but by the territorial states. The new political powers needed a trained framework for the development and construction of their political and ecclesiastical administration. In the rebellious Northern Netherlands this need was even greater than in the German states and states, which had acquired the right to build their own country church with the Peace of Augsburg and for which the university was an instrumentum dominationis , a means of rule and the exercise of power.

In the early modern period it was self-evident that the church was one of the most important order-keeping elements and every government was concerned about its structure, layout and staff. This caused major problems in the Republic. The Protestant movement in the Netherlands was divided between a moderate and a radical wing. The first, humanist and erasmian inspired, stood in front of a broad church, with great dogmatic freedom, in which people with different spiritual interests would feel at home. The radicals wanted a Calvinist church that would organize and discipline the lives and teachings of believers. The conflict between the two movements, which ultimately involved the entire state organization, was the sharpest in Holland.

In Friesland, on the other hand, church stands worked closely together when the university was founded. That had various causes. Leiden was established at the time of the preparations for the Pacification of Ghent, aiming for a compromise between the various regions that would unite the Netherlands against the lord (Philips II): the last major attempt by the moderates to maintain peace.

The foundation of Franeker took place after the failure of the Pacification and the “betrayal of Rennenberg”, the stadholder of Groningen who brought that province back under the rule of Spain. The radicals had the wind in their sails. The time difference is evident in the formulations at the start. With a pious lie, Leiden still appealed to the name of Philips II, Franeker was founded by the sovereign States of Friesland.

Moreover, the family and church leaders in Friesland were much more closely connected with family ties, friendship and shared experiences such as exile than in Holland. They formed a resolute minority with the same ideals. The University of Franeker was founded as one of the means in a civilization offensive aimed at the rapid Protestantization of Friesland and the discipline and rationalization of the lives of the people. Humanism and Calvinism were able to work together well in this endeavor.

The church wanted a modern, scientific education for its pastors, with a study of the Bible in the basic languages. The University of Franeker, like that in Leiden, had a distinctly humanistic character. The artes faculty, which formed a compulsory prior education for the three higher faculties, was the core. Languages and philosophy were taught there, with a strong practical and utilitarian approach. All students had to be trained here to actively master language and texts, so that they could analyze special problems and process them in an argument that focused on conviction. They could follow the education of the higher faculties in this well-equipped way, and then, well-spoken and erudite, serve society.

Conversely, humanism was able to find many of its ideals in Calvinism. Both movements shared a horror of external religious acts, superstitious religious representations and the uncontrolled aspects of folk culture. The mixture of humanistic and Calvinistic elements and the cooperation of the ecclesiastical and political elite gave the ideal that underpinned the founding of Franeker University its strength. In a petition to the States of Friesland in 1603, professor Auletius was able to summarize this ideal: “At the same time you wanted to ensure that the State itself, by completely eradicating all abuses, would come close to the beauty of Christ’s Church.”

Yet the training of pastors was one of the most important tasks of the young university. Since, as was well known at the time, “no one who studies his own good desires to serve the Kercken”, this task required a system of scholarships and a mana in which poor students were fed for free or for a small fee. These institutions were also important for attracting foreign students: in the eyes of time, an essential part of every university. The training that the student obtained at the university made him a member of an international scholarly community and preferably had to be concluded by a tour of various foreign universities.

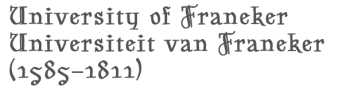

During the first century and a half of its existence, Franeker University succeeded in acquiring such an international character. Of the approximately 15,000 students who registered during the nearly 250 years that the university existed, one third came from abroad and one quarter from other provinces of the Republic. The foreign students mainly came from the German Empire, the countries around the Baltic Sea and the North Sea and from Hungary and Transylvania. Geographical proximity and – especially in the case of Hungarians – religious affiliation were determining factors. The origin of the one hundred and seventy-seven professors who the.

University have confirmed the international element. More than a hundred were from outside Friesland and about a third from outside the Republic.

However, the decline is also evident from the statistics of students and professors. The university grew until 1660. Afterwards, only interrupted by a brief revival around 1700, it gradually went downhill. The students took off, there were fewer foreigners, and the quality of the training dropped. Attempts to stop the decline consisted mainly of the appointment of famous teachers. All too often they went elsewhere. In the second half of the eighteenth century, Franeker was only a provincial institution.

The causes of the decline were of a different nature. All early modern universities suffered a decline in the eighteenth century. Not only Franeker, but also the other universities of the Republic were less visited by foreign students. The international orientation was no longer achieved through personal contacts and an academic tour, but with the help of the new scientific journals, membership of scientific academies and scholarly societies. They studied more in their own country throughout Europe. The nationalization of learning was accompanied by a decrease in the use of Latin.

These developments mark the decline of the humanistic educational ideal. The parts of the arts faculty, originally a coherent whole to convey a general erudition, became independent disciplines into special disciplines, which were mainly characterized by technical mastery. The faculty largely lost its character as a propaedeutic year for the higher

faculties, which provided training for all students.

This change, which required a completely different type of university, was not noticed by the directors of the university in Franeker. That was no coincidence. The decline of Franeker University was exacerbated by special circumstances specific to the Republic and Friesland. The organic conception of the state, church, and university that was at the basis of the founding of Franeker lapsed when the various social movements that formed the young Republic became independent. The big loser was the church.

The last attempt to put the university at the service of the original social reforming ideal came from the professors Ames and Amama, at the end of the twenties of the seventeenth century. Their attempt failed: the church developed in a doctrinal direction and looked carefully at developments at the university. In 1639 she took the exams of the ministers in her own hands. Until then, the church had left them to the theological faculty, over which it had no formal influence.

Of course, that freedom had good consequences for the university. The development of the arts faculty was characterized less than elsewhere by conflicts with orthodoxy. The church in Friesland was under strong control of the state after 1672 and the regents conducted a tolerant policy, which further weakened the position of the ruling church. Newer trends, such as Descartes’ philosophy, were able to gain a foothold at the university. After 1660, Franeker was the most Cartesian of Dutch universities. In the eighteenth century, empirical influences even led to a theoretically formulated natural science research program.

However, the organization of the university lagged behind this development. The power of the regents, who made university freedom possible by expanding the church influence, led to a social rigidity and cultural impoverishment that prevented an adaptation of the university. More than anywhere else in Friesland, political power became concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer families, who separated themselves from the rest of society. The cultural emphasis shifted more to status and decorum and to maintaining the existing. University education became confirmation of status and less a possibility for social mobility.

In the eighteenth century, the trustees – from the circle of regents – did not make any money available for a set of instruments that could have realized the theoretical impetus for modern scientific research. The number of teachers at the arts faculty, where the actual renewal took place, was reduced. Their other policy, which was aimed at maintaining the humanist Protestant signature of the university, was also not very effective. Vacancies were slowly filled by the very formalistic appointment procedures.

The bundle gives an excellent image of a university that has long been an international intellectual and cultural center and which eventually lost its way in a confusing society. Even the imperial committed Cuvier recognized the past glory in his report on the state of the Dutch education that would lead to the abolition: “Comment les sciences et les lettres auraient-elles pénétré jusqu’aux bords marécageux brumeux et de la Mer du Nord , isolate the rest of the continent, sans les établissements de Franéker et de Groningue?

Source:

GT Jensma et al. (Eds.), University of Franeker 1585-1811. Contributing to the history of the Friese Hogeschool, Leeuwarden 1985

Peter van Rooden

NRC / Handelsblad 09/26/1985